The Newfoundland dog has long inspired painters with its striking combination of strength, gentleness, and a noble spirit that seems almost larger than life. From formal royal portraits to dynamic scenes of canine companionship and adventure, the Newfoundland has found a special place in the history of art. The following exploration examines several notable works that celebrate this remarkable breed, revealing not only the evolution of artistic style but also the enduring cultural appeal of the Newfoundland dog. As Byron said, they possess:

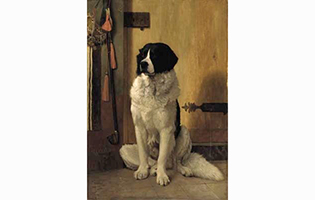

In 1803, British master George Stubbs captured the dignified essence of the Newfoundland in his work, Portrait of a Newfoundland Dog, the Property of H.R.H. the Duke of York. In this formal portrait, Stubbs presents the dog with a measured elegance that reflects its association with royalty. The meticulous rendering of the dog’s robust physique and alert expression speaks to both the breed’s utilitarian background and its refined character—a duality that resonated with an aristocratic audience.

In 1803, British master George Stubbs captured the dignified essence of the Newfoundland in his work, Portrait of a Newfoundland Dog, the Property of H.R.H. the Duke of York. In this formal portrait, Stubbs presents the dog with a measured elegance that reflects its association with royalty. The meticulous rendering of the dog’s robust physique and alert expression speaks to both the breed’s utilitarian background and its refined character—a duality that resonated with an aristocratic audience.

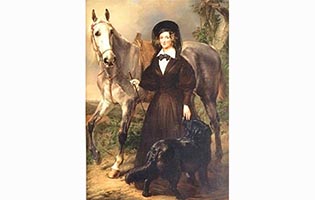

Just a few years later, in 1807, German painter Peter Edward Stroehling contributed to the breed’s artistic legacy with Frederica, Duchess of York. Although the painting centers on the Duchess herself, the inclusion of a Newfoundland dog in the composition underscores the animal’s status as a companion worthy of nobility. The careful balance of portraiture and narrative detail in Stroehling’s work mirrors the cultural esteem in which the breed was held, linking the canine’s physical presence to the ideals of loyalty and grace.

At the dawn of the 20th century, John Emms’s 1906 painting Dogs Watching Bathers captures the Newfoundland dog in a more informal and playful context. In this work, the animal’s gentle yet alert demeanor is highlighted as it observes human activity with a watchful interest. Emms’s choice to place the dog in a scene of leisure and interaction reflects a shift in artistic focus—from formal portraiture to depictions that celebrate the everyday bonds between humans and their animal companions.

At the dawn of the 20th century, John Emms’s 1906 painting Dogs Watching Bathers captures the Newfoundland dog in a more informal and playful context. In this work, the animal’s gentle yet alert demeanor is highlighted as it observes human activity with a watchful interest. Emms’s choice to place the dog in a scene of leisure and interaction reflects a shift in artistic focus—from formal portraiture to depictions that celebrate the everyday bonds between humans and their animal companions.

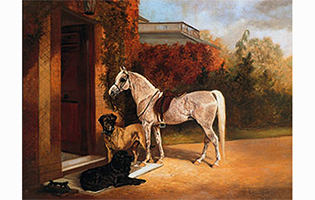

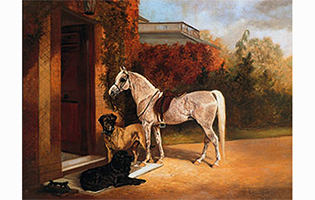

Arthur J. Batt’s 1881 work, Horse, Mastiff and Newfoundland, now housed at the AKC Museum of the Dog, offers a compelling narrative of the animal’s role within a broader domestic and rural context. By juxtaposing the Newfoundland with a horse and a mastiff, Batt creates a dynamic ensemble that speaks to the varied roles dogs played in 19th-century life. The painting’s robust composition and earth-toned palette underscore the Newfoundland’s inherent strength and gentle nature—a combination that made it a favorite among both working families and the nobility.

Arthur J. Batt’s 1881 work, Horse, Mastiff and Newfoundland, now housed at the AKC Museum of the Dog, offers a compelling narrative of the animal’s role within a broader domestic and rural context. By juxtaposing the Newfoundland with a horse and a mastiff, Batt creates a dynamic ensemble that speaks to the varied roles dogs played in 19th-century life. The painting’s robust composition and earth-toned palette underscore the Newfoundland’s inherent strength and gentle nature—a combination that made it a favorite among both working families and the nobility.

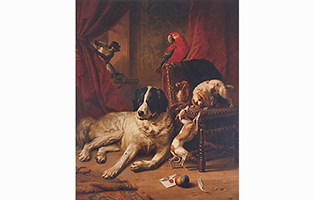

In the more intimate realm of domestic portraiture, the work Portrait of Two Boys with their Newfoundland Dog by Reinagle (Ramsay Richard Reinagle, 1775–1862) celebrates the close bond between children and their canine friend. This tender portrayal encapsulates the warmth, loyalty, and gentle protectiveness for which the Newfoundland is renowned. The painting not only highlights the breed’s physical grandeur but also its role as a beloved member of the family—a theme that has continued to resonate with audiences over the centuries.

In the more intimate realm of domestic portraiture, the work Portrait of Two Boys with their Newfoundland Dog by Reinagle (Ramsay Richard Reinagle, 1775–1862) celebrates the close bond between children and their canine friend. This tender portrayal encapsulates the warmth, loyalty, and gentle protectiveness for which the Newfoundland is renowned. The painting not only highlights the breed’s physical grandeur but also its role as a beloved member of the family—a theme that has continued to resonate with audiences over the centuries.

Together, these works form a tapestry of artistic expression in which the Newfoundland dog is portrayed as much more than a mere subject. In the hands of painters like Stubbs, Stroehling, Nelson, Gérôme, Emms, Batt, and Reinagle, the Newfoundland emerges as a symbol of loyalty, nobility, and the profound relationship between humans and their animal companions. Whether depicted in the grandeur of a royal portrait or in the simplicity of a family scene, the Newfoundland dog continues to capture the imagination of artists and audiences alike.

The evolution of its depiction—from the stately formality of early portraits to the dynamic and intimate studies of later centuries—mirrors broader changes in art and society. Through these varied representations, the Newfoundland dog has earned its place not only in the annals of canine history but also in the rich tradition of animal portraiture, where its legacy endures in every brushstroke.