excerpt from: Stories About Dogs: Illustrative of their Instinct, Sagacity and Fidelity, illustrated by engravings by Thomas Landseer

published by Dean & Trevitt NY, 1841

SECOND EVENING.

UNCLE THOMAS TELLS ABOUT THE NEWFOUNDLAND DOG, AND RELATES MANY STORIES ILLUSTRATIVE of ITS WONDERFUL SAGACITY AND INSTINCT.

" WELL, boys, I am glad you have come early to-night, as I have some long stories to tell you."

" Oh, very well, Uncle Thomas; we are very happy to hear that. But mama bid me say that she was afraid we troubled you too much by coming so very often."

" Not at all, Frank. Give my love to mama, and tell her that it gives me quite as much pleasure to tell you the stories, as it gives you to listen to them. I love to tell stories to good boys, and I have such a store left that there is no fear of their being exhausted."

"Thank you, Uncle Thomas. You are so kind!"

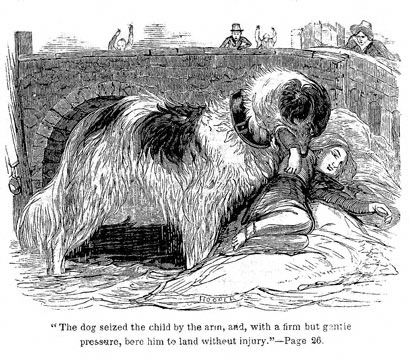

" Stay, boys, stay. If we go on bandying compliments, I am afraid we shall hardly get through all the stories I intended to tell you to-night. But before I begin I must show you a picture which I have in my portfolio. It is an engraving of a Newfoundland dog pulling a boy out of the water."

"Oh, Uncle Thomas! But is the little boy drowned ?" "No, Harry, he was not drowned, thanks to the readiness and sagacity of the fine dog which came to his rescue. The little fellow had gone to the pond to sail his tiny ship, and in leaning down to pull it out of the water, he overbalanced himself and fell headlong into a deep pool, and would certainly have been drowned but for Sancho's assistance. His screams alarmed his mother, she ran to the spot, and had the satisfaction to receive her dear little son, uninjured, though terribly frightened."

"How fortunate that the dog happened to he at hand!" "It was, indeed. I have heard another story of the same kind."

“Pray do let us, hear it, Uncle Thomas."

"One day, as a girl was amusing herself with an infant, at Aston's Quay, near Carlisle Bridge, Dublin, and was sportively toying with the child, it made a sudden spring from her arms, and in an instant fell into the Liffey. The screaming nurse and anxious spectators saw the water close over the child, and conceived that he had sunk to rise no more. A Newfoundland dog, which had been accidentally passing with his master, sprang forward to the wall, and gazed wistfully at the ripple in the water, made by the child's descent. . At the same instant the child reappeared on the surface of the current, and the dog sprang forward to the edge of the water. Whilst the animal was descending, the child again sunk, and the faithful creature was seen anxiously swimming round and round the spot where it had disappeared. Once more the child rose to the surface; the dog seized him, and with a firm but gentle pressure bore him to land without injury. Meanwhile a gentleman arrived, who, on inquiry into the circumstances of the transaction, exhibited strong marks of sensibility and feeling towards the child, and of admiration for the dog that had rescued him from death. The person who had removed the babe from the dog turned to show the infant to this gentleman, when it presented to his view the well-known features of his own son! A mixed sensation of terror, joy, and surprise, struck him mute. When he had recovered the use of his faculties, and fondly kissed his little darling, he lavished a thousand embraces on the dog, and offered to his master a very large sum (500 guineas) if he would transfer the valuable animal to him; but the owner of the dog (Colonel Wynne) felt too much affection for the useful creature to part with him for any consideration whatever."

"One day, as a girl was amusing herself with an infant, at Aston's Quay, near Carlisle Bridge, Dublin, and was sportively toying with the child, it made a sudden spring from her arms, and in an instant fell into the Liffey. The screaming nurse and anxious spectators saw the water close over the child, and conceived that he had sunk to rise no more. A Newfoundland dog, which had been accidentally passing with his master, sprang forward to the wall, and gazed wistfully at the ripple in the water, made by the child's descent. . At the same instant the child reappeared on the surface of the current, and the dog sprang forward to the edge of the water. Whilst the animal was descending, the child again sunk, and the faithful creature was seen anxiously swimming round and round the spot where it had disappeared. Once more the child rose to the surface; the dog seized him, and with a firm but gentle pressure bore him to land without injury. Meanwhile a gentleman arrived, who, on inquiry into the circumstances of the transaction, exhibited strong marks of sensibility and feeling towards the child, and of admiration for the dog that had rescued him from death. The person who had removed the babe from the dog turned to show the infant to this gentleman, when it presented to his view the well-known features of his own son! A mixed sensation of terror, joy, and surprise, struck him mute. When he had recovered the use of his faculties, and fondly kissed his little darling, he lavished a thousand embraces on the dog, and offered to his master a very large sum (500 guineas) if he would transfer the valuable animal to him; but the owner of the dog (Colonel Wynne) felt too much affection for the useful creature to part with him for any consideration whatever."

"That is quite astonishing, Uncle Thomas; it almost seems as if some dogs could act with the intelligence of human beings."

"The Newfoundland dog, to which both these stories refer, is, perhaps, the noblest animal of the whole race. In sagacity he is little if at all inferior to the Alpine spaniel. When of a good full-sized breed, he measures upwards of six feet from the muzzle to the point of the tail, and stands nearly three feet in height. He seems to take delight in bearing the burdens and watching over the safety of man. Nothing pleases him so much as being employed, carrying a stick or basket for miles in his mouth, guarding his charge with most unflinching courage and integrity. While engaged in his master's work, no personal insult can induce him to forego his charge. If his assailant is puny and insignificant, he despises it, passes on, and forgets the injury; but if he deems it a worthy antagonist, having discharged his duty, he returns and takes terrible vengeance.

" A gentleman who lived at a short distance from a village in Scotland, had a very fine Newfoundland dog, which was sent every forenoon to the baker's shop in the village, with a napkin, in one corner of which was tied a piece of money, for which the baker returned a certain quantity of bread, tying it up in the napkin and consigning it to the care of the dog.

At about equal distances from the gentleman's mansion there lived two other dogs; one a mastiff, which was kept by a farmer as a watchdog; and the other a stanch bull-dog, which kept watch over the parish mill. As each was lord-ascendant, as it were, over all the lesser curs of his master's establishment, they were each very high and mighty animals in their way, and they seldom met without attempting to settle their precedence by battle.

Well, it so happened that one day, when the Newfoundland dog was returning from the baker's with his charge, he was set upon by a host of useless curs, who combined their efforts, and annoyed him the more that, having charge of the napkin and bread, he could not defend himself, and accordingly got himself rolled in the mire, his ears scratched, and his coat soiled.

Having at length extricated himself, he retreated homeward, and depositing his charge in its accustomed place, he instantly set out to the farmer's mastiff. To the no small astonishment of the farmer's family, instead of the meeting being one of discord and contention, the two animals met each other peacefully, and after a short interchange of civilities, they both set off towards the mill. Having engaged the miller's dog as an ally, the three sallied forth, and taking a circuitous road to the village, scoured it from one end to the other, putting to the tooth, and punishing severely, every cur they could find. Having thus taken their revenge, they washed themselves in a ditch, and each returned quietly to his home. They never met, however, without a renewal of their old feud, fighting against each other as if such a league had never been formed."

"Really, Uncle Thomas, I can't think how the Newfoundland dog told the mastiff what he wanted. Have dogs a language of their own, do you think?"

"That is a question, John, which I am not able to answer. That they have not what may properly be called a language is plain enough; that is, they have no fixed sounds by which to communicate their thoughts or their wishes to each other but that they can make themselves intelligible to one another, cannot be denied. Philosophers have speculated about it, John, but we are still quite as much in the dark in regard to it as we are about instinct."

"The faculty by which animals communicate their wants to each other is, however, so singular, that I must tell you another story illustrative of it. At Horton, in Buckinghamshire, where the poet Milton passed some of his early days, a gentleman from London a few years ago took possession, of a house, the former tenant of which had removed to a farm about half a mile off. The new tenant brought with him a large French poodle, to take the duty of watchman, instead of a fine Newfoundland dog, which went away with its master, but a puppy of the same breed was left behind, and he was incessantly persecuted by the poodle. As the puppy grew up, the persecution continued. At length he was one day missing for some hours, but he did not come back alone, he returned with his old friend the large house-dog; to whom he had communicated his hardships, and in an instant the two fell upon the unhappy poodle, and killed him, before he could be rescued from their fury.

I have a great many more stories about dogs communicating their ideas to each other, but I think I have told you enough for the present. There is one story, however, which is so curious, from the fact of the aggrieved animal travelling a very long distance in search of assistance, that I cannot pass it over .

"A gentleman from Scotland arrived at an inn in St. Albans, on his way to the metropolis, having with him a favourite terrier dog; and being apprehensive of losing him in London, he left him to the care of lhe landlord, promising to pay for the animal's board on his return, in about a month or less. During several days the dog was kept chained, to reconcile him to the superintendence of his new master; he was then left at liberty to range the public yard at large with others. There was one amongst his companions which chose to act the tyrant, and frequently assaulted and bit poor Tray unmercifully. The latter submitted with admirable forbearance for some time, but his patience being exhausted, and oppression becoming daily more irksome, he quietly took his departure. After an absence of several days, he returned in company with a large Newfoundland dog, made up directly to his tyrannical comrade, and, so assisted, very nearly put him to death. The stranger then retired. and was seen no more, and Tray remained unmolested until the return of his master.

"The landlord naturally mentioned a circumstance which was the subject of general conversation, and the gentleman heard it with much astonishment, because he suspected that the dog must have travelled into Scotland to make known his ill treatment, and to solicit the good offices of the friend which had been the companion of his journey back, and his assistant in punishing the aggressor. It proved to have been so for on arriving at his house in the Highlands, and inquiring into particulars, he found, as he expected, that much surprise and some uneasiness had been created by the return of Tray alone; by the two dogs, after meeting, going off together; and by the Newfoundland dog, after an absence of several days, coming back again foot-sore and nearly starved,"

"What a pity it was that the mastiff and the Newfoundland dog continued enemies! Do dogs that once fight always hate each other?"

"No, boys, I am happy to say they do not, as I can prove to you by an instance. One day a Newfoundland dog and a mastiff, which never met without a quarrel, had a fierce and prolonged battle on the pier of Donaghadee, and from which, while so engaged, they both fell into the sea. There was no way of escape but by swimming a considerable distance. The Newfoundland being, an expert swimmer, soon reached the pier in safety; but his antagonist, after struggling for some time, was on the point of sinking, when the Newfoundland, which had been watching the mastiff's struggles with great anxiety, dashed in, and seizing him by the collar, kept his head above water, and brought him safely to shore. Ever after the dogs were most intimate friends; and when, unfortunately, the Newfoundland dog was killed by a stonewaggon passing' over his body, the mastiff languished, and evidently lamented his friend's death for a long time."

"The Newfoundland dog seems to be a capital swimmer, Uncle Thomas. How is it that he swims so much better than most other dogs?"

"Partly from the construction of his foot, which is what is called webbed; that is, a thin skin stretches between the toes, as you see in the duck's foot. It is thus enabled to make its way with so much more ease in water than those whose feet are not so formed. Besides, in taking to the water naturally, as we say, it only follows an instinct with which the Creator has endowed it, no doubt for the wisest and best purposes.

“Most of the stories which I have to tell you about the Newfoundland dog turn upon his saving persons from drowning. I remember a curious one in which his zeal to save his master was the cause of his losing a bet, which I think will amuse you.

"A Thames waterman once laid a wager that he and his dog would leap from the centre arch of Westminster Bridge, and land at Lambeth within a minute of each other, He jumped off first, and the dog immediately followed; but as it was not in the secret, and fearing that its master would be drowned, it seized him by the neck, and dragged him on shore, to the no small diversion of the spectators."

"There is a story, Uncle Thomas, which you once told me about a gentleman slipping into a river, and being drowned, but who was brought on shore by his dog, and recovered by the kind treatment of some peasants. I tried to repeat it to John and Harry, but as I found I could not get on, I promised to ask you to tell it to them. Will you have the kindness to repeat it to us, Sir?"

"Oh! I recollect the story you mean, Frank. I will repeat it with pleasure, as it affords a very fine instance of sagacity.

A native of Germany, when travelling through Holland, was accompanied by a large Newfoundland dog. Walking along a high bank which formed the side of a dike or canal, so common in that country, his foot slipped, and he fell into the water. As he was unable to swim, he soon became senseless. When he recovered his recollection, he found himself in a cottage, surrounded by peasants, who were using such means as are generally practised in that country for restoring suspended animation. The account given by the peasants was, that as one of them was returning home from his labour, he observed, at a considerable distance, a large dog in the water swimming, and dragging and sometimes pushing something that he seemed to have great difficulty in supporting, but which, by dint of perseverance, he at length succeeded in getting into a small creek.

"When the animal had pulled what it had hitherto supported as far out of the water as it was able, the peasant discovered that it was the body of a man. The dog, having shaken himself, began industriously to lick the hands and face of his master; and the peasant, having obtained assistance, conveyed the body to a neighbouring house, where the usual means having been adopted, the gentleman was soon restored to sense and recollection. Two large bruises with the marks of teeth appeared, one on his shoulder, and the other on the nape of his neck; whence it was presumed that the faithful animal had seized his master by the shoulder and swam with him for some time, but that his sagacity had prompted him to let go his hold, and shift his grasp to the neck, by which means he was enabled to support the head out of the water. It was in the latter position that the peasant observed the dog making his way along the dike, which it appeared he had done for the distance of nearly a quarter of a mile before he discovered a place at which it was possible to drag his burden ashore. It is therefore probable that the gentleman owed his life as much to the sagacity as to the fidelity of his dog."

"That was very wonderful, indeed. I am sure the gentleman would love his dog so!"

"He ought to have done so, Harry, and I dare say loved and cherished him to the end of his life. It is not everyone who can write such an epitaph on a favourite dog as the great Lord Byron did, but I dare say many a one has loved his dog quite as much. I will show you the epitaph by-and-by, but I must first tell you about a dog which, by a wonderful exercise of instinct, returned home from the continent, after the loss of his master.

"A young gentleman purchased a large Newfoundland dog before embarking at a port in the neighbourhood of Edinburgh on a tour on the continent, intending to make it his guardian and companion during his journey. As he was bathing in the river Odder with two of his countrymen, he was unfortunately carried away by the force of the stream, and was drowned. When the dog missed its master it began plunging and diving everywhere in search of him; but at length, wearied out and unable to find him, it returned to the bank, and followed the gentleman's clothes to his hotel. After his portmanteau was made up and sent off to England the faithful animal disappeared, and its loss was mentioned with regret in letters from Frankfort, both from the interest which the case of the young gentleman had excited, and also from the singular sagacity of which the dog had given many proofs.

"At the distance of two or three months after this disastrous affair, the young gentleman's friends were surprised at receiving a visit from the person from whom he had bought the dog, and being informed that it had returned home, but in so worn-out and emaciated a state, that it had since been hardly able to move.

"The circumstance of the dog's return from such a distance excited a good deal of curiosity, and inquiry was immediately set on foot to ascertain how it had travelled. It was ascertained that no ship from the continent had arrived at any of the neighbouring ports, so that it was concluded that this remarkable animal had found its way from Frankfort to Hamburgh, and, embarking on board of some ship for Newcastle or Hull, had travelled thence by land to Edinburgh. The friends of the young gentleman gladly received it under their protection, and showed it all the kindness which its attachment and sagacity so well deserved."

"We know not what to think, Uncle Thomas. Your stories are all so wonderful, that every succeeding one seems to outdo its predecessor."

"Why, Frank, I might go on all night relating such stories, but I must stop for the present. But before you go, John shall read for us the epitaph which Lord Byron inscribed on a pedestal which he raised over his dog Boatswain. It is written, to he sure, in a very bad, misanthropic spirit, but it contains the expression of a great mind for a faithful and attached canine friend. The monument is placed in a conspicuous situation in the garden of Newstead. The verses are preceded by the following inscription:

Near this spot

Are deposited the Remains of one

Who possessed Beauty without Vanity,'

Strength without Insolence,

Courage without Ferocity,

And all the Virtues of Man without his Vices.

This Praise, which would be unmeaning Flattery

If inscribed over human ashes,

Is but a just tribute to the Memory of

BOATSWAIN, a dog,

Who was born at Newfoundland, May, 1803,

And died at Newstead Abbey, Nov. 18, 1808.

“When some proud son of man returns to earth,

Unknown to glory, but upheld by birth,

The sculptor's art exhausts the pomp of woe,

And storied urns record who rests below;

When all is done, upon the tomb is seen,

Not what he was, but what he should have been;

But the poor dog, in life the firmest friend,

The first to welcome, foremost to defend,

Whose honest heart is still his master's own,

Who labours, fights, lives, breathes for him alone,

Unhonour'd falls, unnoticed all his worth,

Denied in heaven the soul he held on earth:

While man, vile insect, hopes to be forgiven,

And claims himself a sole exclusive heaven.

Oh, man! thou feeble tenant of an hour,

Debased by slavery, or corrupt by power;

Who knows thee well, must quit thee with disgust,

Degraded mass of animated dust!

Thy love is lust, thy friendship all a cheat,

Thy smiles hypocrisy, thy words deceit!

By nature vile, ennobled but by name,

Each kindred brute might bid thee blush for shame.

Ye! who perchance behold this simple urn,

Pass on-it honours none you wish to mourn

To mark a friend's remains these stones arise;

I never knew but one,-and here he lies.

Newstead Abbey, November 30, 1808."

“Very good, John. Now, boys, to task your ingenuity, I will give you a Charade, which you can think over till next time we meet, when we shall see which of you can solve it. It was written by Professor Porson, during an evening walk in the neighbourhood of a country village.

My first, though the best and most faithful of friends,

You ungen'rously name with the wretch you despise:

My second-I speak it with grief-comprehends

All the good, and the great, and the just, and the wise:

Of my whole, I have little or nothing to say,

Except that it marks the departure of day."

"Oh, I know it, Uncle Thomas!"

"Very well, Frank, I shall hear your solution to-morrow, if you please. Good night!"